This is the introduction to the book I am currently working on…

(Image of the plan of the garden).

“We are the plans of our ancestors”.

So said the tutor of the Masters course I had signed up to quite late in life. I think he was talking more broadly, but I was at that time, clutching an actual plan - a garden plan that had been drawn by one of my ancestors and recently passed to me by a distant cousin.

The plan was a design of my Great Grandfather’s making. The garden was one I had known as a child – it was in Ealing, West London and I remember the raspberries, and a tree that I think was an apricot at the bottom. But the worn and faded plan showed the full fruitiness of the endeavour – it was packed with apple and pear trees – oh and a cherry that would prove significant – and many currant bushes and berries, not to mention rhubarb.

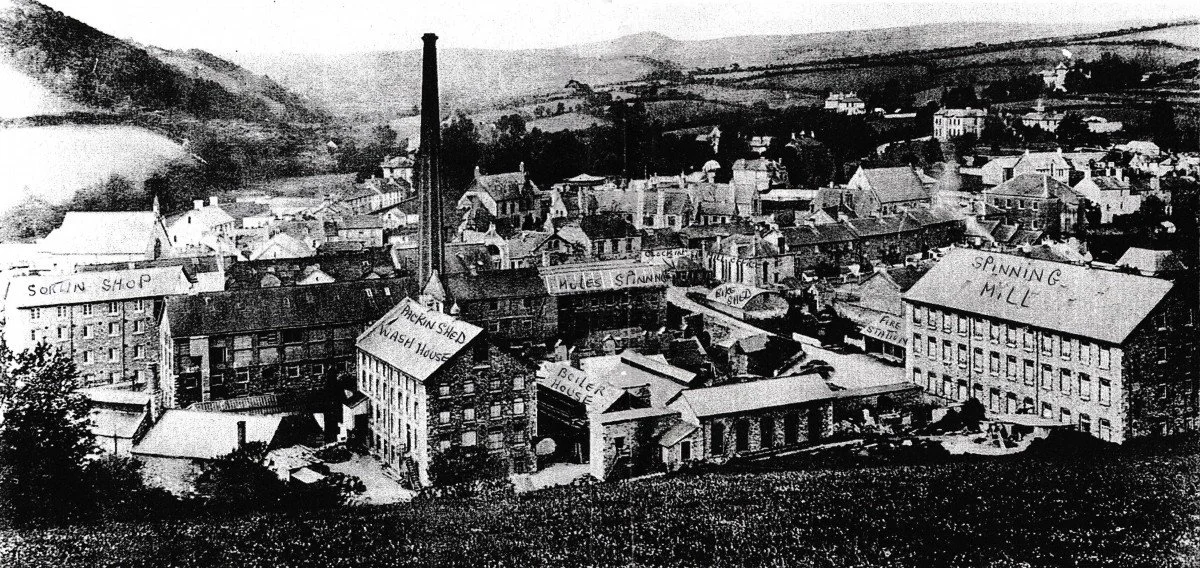

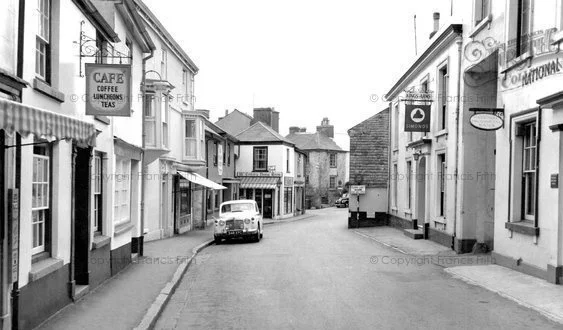

The relative – Sam, had been a gardener in Devon. Living and working close to where I was studying at Dartington, and his quite sudden move from Buckfastleigh to the capital intrigued me. Initially it provided material to study and explore creatively – but quite quickly the subject drew me in. I became a family history nerd, a bore to those who weren’t interested in the happenstances and dramas of my particular tribe.

However, I also started to reflect on how and why we approach the history of those who went before us. Raymond Williams pointed out that each generation is interested not in the times of their parents, but of the generation before – the era of their grandparents. This was not quite my experience, Sam came from the one before that, but it generally held true. Certainly, the bit about being less interested in the lives of my parents. But that was at the start of this journey. As I have worked with my ancestors, so they have led me – first back and then forward again, to consideration of my parents, and myself and my children.

Through various approaches I have tried to place myself alongside these people. By visiting their homes and where possible their gardens, by walking the routes they took from home to work or school. Through reading notebooks and journals. Studying photographs and finding articles in local newspapers or minutes of meetings that they have participated in. I have been given artefacts and tools made or used by relatives. And I have generated creative responses to this material – mainly writing, but also short films and lino cut prints.

The process has felt like dancing with the ancestors. A contact dance of some sort, where sometimes I lead and sometimes the relative leads. I did not set out believing in the agency of spirits, but this process has certainly seen some uncanny interventions, or luck, or auto suggestion at work.

People dance with their ancestors in various ways. Through stories handed down, or well-thumbed family albums. Through cookbooks or bibles that are bequeathed. Through hours spent on one of the public search engines – Ancestry or Find My Past they construct and share their family tree – which can quickly become addictive – I know - I’m a user. But this is book is written not just to chronicle a strangely overlapping set of stories, but to advocate for a physical approach to ancestral research. I describe some of the approaches I have taken, the walks and meetings. The strange enjoyment of just scanning the horizon that my great grandparents scanned 150 years ago. Wondering if the feeling the landscape generates in me, is similar to the feeling it generated in them.

Of course, there is no definitive answer to these wonderings, and part of the dance has included guesses. Or to be more accurate dramatizations. I have taken liberties with the history, but I think they would enjoy these speculations – on the understanding that I am clear their lives were far harder, messier, and definitely more interesting than anything I can fabricate.

In my explanation of this dance I have to explain two time signatures. The chronology of the family history, and the chronology of the process. The information didn’t emerge in the order in which the book Is written – the data coils back in on itself, something comes to light which changes the significance of something that I dealt with previously. The stories wriggle and refuse to sit neatly, the process is dynamic, the ground constantly shifting beneath feet.

And that I think is the point. The process of researching and trying to understand the lives of those who went before is a dynamic and, I believe, a two-way conversation. As I learn about them, so the knowledge and the act of learning changes me. It is not unlike working clay before throwing a pot, or kneading bread before it is baked. Air and life has to be worked into the material. And the act of working affects the muscles and mind of the worker.